MIGRATION POLICY OF EUROPEAN UNION

Melda Belkıs KÜPELİ tarafındanMIGRATION POLICY OF THE EU

Abstract

Following the world’s current issues such as civil wars, instability within countries, inequality in different regions, lack of human rights, and many other global questions to tackle, we have seen a massive movement of people. People who are changing their locations in hopes of opening a new page in their lives caused multiple crises that affected many places around the world. During this period, especially after the Second World War, we have heard of a word which was repeated countless times: migration. The term migration can be defined in different ways, and it can be divided into several categories; most importantly, it can be narrated in divergent ways in which people can induce new emerging ideologies.

On the one hand, when we look back in time, it is clear that the question of migration is nothing new to discuss today; however, it is far more sophisticated and hard to deal with. On the other hand, when we look into the current status quo, it is clear that the migration crisis hit the developed countries the most with dramatic numbers. European Countries that are geographically closer to some of the world’s most tragic events were challenged by all the new incomers and forcibly displaced people. In such a case, what is most striking is the fact that these numbers are not just statistics, but individuals who are gaining migrant status in different ways. Furthermore, the European Member States which are affected the most, are looking for common policies that can work for all member states. In this paper, I will try to comprehend the aftermath of the migration crisis and the Migration Policy, which was the dominant question after the migration crisis.

What is the EU’s migration policy?

Migration has always been a question of security, integration, economy, and many more. Especially after the migration crisis in 2015, the EU and its member states were challenged by all these questions in a small timeframe. The humanitarian side of the crisis urged all the member states to act on it; however, the EU works much more complicated than that. The situation wasn’t handled as successful as it was normatively suggested; therefore, we have seen many refugees stuck at the EU borders. At this point, the EU and its member states intensified their efforts and came up with better yet questionable solutions. To understand the migration policy, we can focus on 3 main circles that are mentioned in the Vienna Action Plan (1998) (Vermeulen, 2019a).

The first and the smallest circle would be the Schengen area since the policy had to deal with the security of the EU borders as well as the allocation of asylum seekers (Vermeulen, 2019b). One of the main advantages of Shengen, which is the freedom of movement, increased the concerns about the EU borders; hence, the first circle of the migration policy aimed to regulate security checks, and ensure member states that Schengen is not a threat.

The second and relatively bigger circle concentrates on the outside EU zone (Vermeulen, 2019c). Countries that are in the Mediterranean region, and also the neighbors to the EU borders like Turkey, Libya, and Morocco are seen as possible partners to host refugee flows (Vermeulen, 2019d). The best example for this circle is the EU-Turkey Statement & Action Plan agreement that was reached in 2016. Following the agreement in 2018, Turkey received about €3bn for taking care of the refugees (Council of the EU, 2018). These efforts did help the EU in terms of reducing illegal migrants; however, it made the whole migration policy questionable. Although the crisis brought instability within EU member states, many argued that the union chose the easy way out by leaving the refugee burden to developing countries.

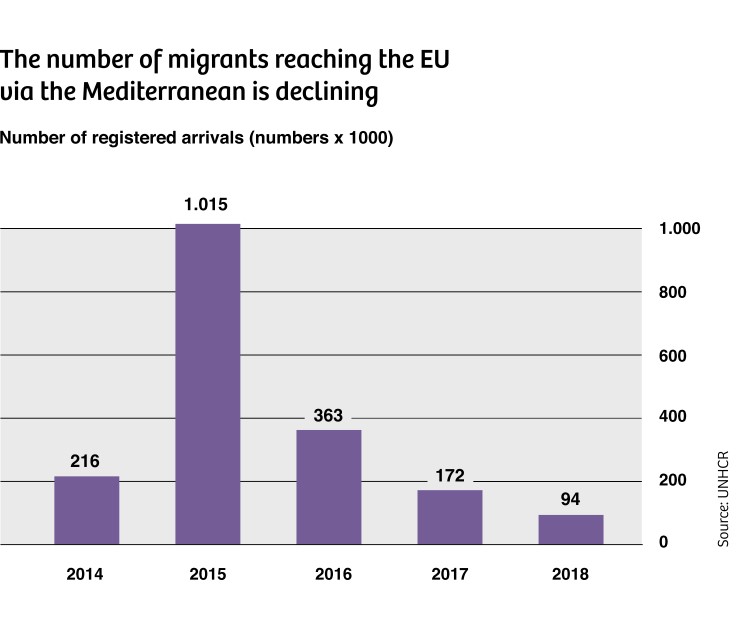

Final and the third circle includes countries that are on a wider range, countries which are where the migrants come from (Vermeulen, 2019e). The policy consists of return agreements as well as project fundings that aim to demotivate migrants to travel to Europe (Vermeulen, 2019f). The second and third circles got more attention by the time since many of the European member states didn’t even want to consider migration flows to enter their borders. After all the measures that the EU took, the EU decreased the number of irregular arrivers by 90% (European Council, 2019).

How did EU member states respond to the migration policy?

The outcomes of the EU migration policy can vary in different fields and different member states. Since the migration flows continue to hit some EU member states more than the other ones, it is also hard to equally distribute all the newcomers. One of the biggest debates on this topic is the shifting role of some of the member states. Member States like Hungary, Czech Republic, and Poland were member states that refused to take responsibility. In response to these countries’ decisions, the European Commission charged these three member states of "non-compliance with their legal obligations on relocation" (BBC, 2017). Furthermore, Al Jazeera (2019), reports that „The European Commission has referred Hungary to the European Court of Justice over controversial laws that restrict people's right to request asylum and make it a criminal offense to help refugees and migrants.”

Another example for member states that are not in favor of the migration policies of the EU would be the UK. Especially after the migration crisis, and the new measures that were agreed upon to cope with the crisis, the shifting politics were in the scene. During the Brexit referendum stage, we have seen many anti-migrant and anti-refugee sentiments emerging in British politics. When the Brexit got out of the referendum in 2016; however, things took a big turn for the UK. It was unexpected both by the European Union and for almost half of the UK’s citizens.

Besides political disagreements with the mentioned member states, the EU also has countries that are the first stop for refugees. According to Vermeulen (2019), “The Common European Asylum System (CEAS) was hammered out in 2013, unifying asylum procedures across Europe. One part of the CEAS is the now notorious Dublin Regulation, which decrees that a migrant may only apply for asylum in the country where they entered the EU. As a result, southern European countries have to process far more asylum applications than northern European countries – after all, migrant boats land on the Mediterranean coast.”

Since the majority of these refugees can’t be reallocated fast enough after their arrivals to the southern European countries, there had been serious human rights violations that took place in countries like Greece and Italy. In some cases, refugee boats were not even aided by their coastal security. In Greece, the problem of hosting refugees got quite crucial, and the refugee camps became overcrowded. Greece didn’t provide hygienic conditions nor sanitary facilities to the refugees. Besides, such basic needs as medical or psychosocial support weren’t given; moreover, less than 15 percent of asylum-seeking children had access to education in the camps (Human Rights Watch, 2019). Greek politicians demanded sanctions be imposed on EU member states that refuse to take migration quotas (The Guardian, 2019).

How successful is the EU migration policy?

An answer to this specific question can change from different perspectives. When it comes to measuring the success level, one of the main struggles depends on what is considered as successful. Comparing today's numbers of arrival to 2015, it may seem like the number is going downwards; nevertheless, it doesn't mean that today's numbers are preferable. In summer 2015, tens of thousands of people flee from Syria, Iraqis and Afghans flee from terrorist groups such as IS and the Taliban, and after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi warring militias in Libya started to organize smuggling better (Vermeulen, 2019g). A massive flow following all these events shook the EU so much that now we see tendencies of considering today's big numbers as acceptable.

About the crisis of solidarity on migration, it can be suggested that the EU failed miserably. The migration policy underlines the importance of a united Europe in which countries share each other's burdens; even so, the aftermath of the migration crisis proved that it is way harder in practice. A very good example can be France, a country that is highly devoted to the EU. In recent elections, even in a very European country like France, the results were given the hints of dissatisfaction of the union.

About the crisis of solidarity on migration, it can be suggested that the EU failed miserably. The migration policy underlines the importance of a united Europe in which countries share each other's burdens; even so, the aftermath of the migration crisis proved that it is way harder in practice. A very good example can be France, a country that is highly devoted to the EU. In recent elections, even in a very European country like France, the results were given the hints of dissatisfaction of the union.

From the human rights perspective, there are violations besides some achievements. As mentioned earlier, the human rights situation in southern European countries is nowhere close to high European standards. In Germany, on the other side, Angela Merkel used the now-iconic words "Wir schaffen das" – we’ll manage this – to give the message that Germany is welcoming the refugees. According to UNHCR (2019), Germany is the top refugee-hosting country in the European Union. On the contrary of the positive expectations Germany sets, Angela Merkel started to get criticized harshly, and the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany gained votes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no way to deny that there are some efforts to solve the migration crisis; however, the scale of the efforts are not covering the issues. People who lost their lives in the Mediterranean Sea cannot be put aside. Countries shouldn’t need Aylan Kurdis to act on the migration crisis. It is also significant to realize public reaction to migration policies. The growing far-right sentiments and nationalist patterns made political damages to the European Union, and now the European citizens are concerned. Rising populism and right-wing movements cannot be ignored in a European Union, which aims a more integrated continent.

The migration policy of the EU aims to handle the crisis in a way that Europe can benefit the most, yet it is also essential not to leave all the burden on the developing countries' shoulders. The ‘’keep the chaos away no matter where’’ kind of policy would end up with another crisis that eventually hits the European Union again. All in all, migration will never end; thus, it is in the power of countries to take responsibility and manage it according to The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. If the EU is very confident to set human rights standards, then it also has to be confident enough to implement what is set.

References:

Vermeulen, M. (2019a, b, c, d, e, f, g). 10 questions that explain the European Union’s migration policy. Retrieved 26 December 2019, from

https://thecorrespondent.com/93/10-questions-that-explain-the-european-unions-migration-policy/12299086041-3a16f02d

Council of the EU. (2018). Facility for refugees in Turkey: member states agree on details of additional funding. Retrieved 26 December 2019, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/06/29/facility-for-refugees-in-turkey-member-states-agree-details-of-additional-funding/

European Council. (2019). EU migration policy. Retrieved 26 December 2019, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/migratory-pressures/

BBC. (2017). EU to sue Poland, Hungary and Czechs for refusing refugee quotas. Retrieved 27 December 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-42270239

Al Jazeera. (2019). European Commission takes Hungary to court over migrant law. Retrieved 27 December 2019, from

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/european-commission-takes-hungary-court-migrant-law-190726063518691.html

The Guardian. (2019). Greek PM: EU states must do more to share the burden of hosting refugees. Retrieved 27 December 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/04/greek-pm-eu-states-must-do-more-to-share-burden-of-hosting-refugees

Human Rights Watch, (2019). European Union Events of 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2019, from https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/european-union

UNHCR. (2019). Figures at a Glance. Retrieved 27 December 2019, from https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

Melda Belkıs KÜPELİ

Güney Güvenlik Okulu Asya-Pasifik Masası Sorumlusu.