JAPAN'S ENERGY

Melda Belkıs KÜPELİ tarafındanABSTRACT

Today, energy is a top priority for most countries. It is noteworthy that a balanced demand and supply of energy is desirable for every energy consumer. There are various researches made in this sector, trying to answer the questions over how to achieve that balance, and where different countries are on that scale. By reviewing fundamental research topics and by analyzing various reports on the energy of Japan, I have concluded that Japan, as one of the world’s most comprehensive consumers of energy, has certain challenges to deal with. As a result of the situation, within the Japanese energy policy, there are exercises to handle these hardships. From its projects over renewable energy to the revival of nuclear plantations, Japan is dedicated to reaching progress on its energy future.

1. INTRODUCTION

Japan is one of the worlds' highly developed countries, with a big economy and a large population. With a GDP of $5.15 trillion (World Population Review, 2020), which makes Japan the third-largest economy in the globe, as well as its large population of 126.325.272 (Worldometer, 2020), as Japan continues to spin its economic wheel, its energy demand will always stay persistent.

Even though Japan has a promising development within many spheres of the global market, there are visible challenges in front of Japan from various viewpoints. Whether these challenges are caused by the coronavirus pandemic, natural disasters, regional conflicts, or they are a long-term consequence of its aging population, Japan has to confront them at some point.

Considering where Japan is today as an energy importer and consumer combined with where it projects to be in the future, there are efforts to keep the Japanese energy supply steady. By analyzing different data and information on Japan's energy profile, in this paper, I will be drawing a picture of Japan's energy as well as looking at Japan's attempts to solve its problems in the fight to save its energy outlook.

2. JAPAN AS AN ENERGY CONSUMER

Japan, as its developed counterparts across the globe, is dependent on different types of energy imports to meet its needs. In 2019, Japan ranked as the 3rd largest coal importer, 4th largest crude oil importer, 5th largest oil consumer, and the world's largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) importer (EIA, 2020). The same analysis also underlines the fact that Japan counts heavily on its international cargo tankers and their shipment of crude oil along with LNG since Japan is not a part of any natural gas or oil pipelines which can provide foreign resources.

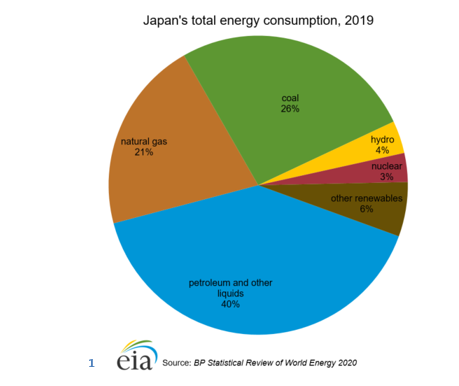

The graph above demonstrates that Japan’s energy consumption is mainly made out of fossil fuels that are imported comparatively. In 2019, as the second graph below indicates, the numbers have stayed close to 2017’s outlook. These numbers show that there were not enough resources domestically to replace the imports between the years of 2017 and 2019.

To comprehend Japan as an energy consumer, it is crucial to understand Japan's energy policy as well as the struggles that are challenging these policies.

What are Japan's Energy Challenges?

As there are many success stories on Japan's energy policy, there are also many challenges to it that await to be solved. After the end of the Second World War, Japan transformed itself into a fast-growing economy through its rapid industrial development. The Japanese government was granting money for various projects (including energy-focused projects) on top of carrying its protectionist policies while enjoying its economic boom.

According to Tripp (2017), ''This potent mix of economic factors led the way to Japan becoming the world’s 3rd largest economy until in the mid-1990’s when the USA and other countries demanded that Japan cease it protectionist ways, allow the Yen to float on the open market, and truly open their economy.'' The peaking of the stock market in 1989 and the collapse of it during the 1990s shook the Japanese economy considerably (Kanaya and Woo, 2000, p.8). This era of the lost decades shoot up the prices of the energy resources as well as many other goods, escalated the situation; moreover, left Japan with difficulties that can be seen even today.

Beyond economic struggles within Japanese history, there are current strains such as the aging population in Japan as in many other developed countries. In September 2020, the proportion of people who were older than 65 was the highest among other countries, with a percentage of 28.7 of the whole population, which makes up for 36.17 million people (The Japan Times, 2020).

These trends over demographics in Japan point at the economy with declined growth every year. The combination of the aging population and the shrinkage caused by the drops in fertility rates hamper the Japanese economy (Walia, 2019). The older the generations get, the less the country becomes productive, which in the end affects the Japanese energy productivity as well as consumption.

Putting its economic and demographic challenges aside, one of the most striking obstacles for Japanese energy is the natural challenges Japan has to cope with. Natural disasters happen quite often in Japan, from severe weather conditions to sudden earthquakes, Japan is suffering from many dangers due to its location in the Pacific earthquake belt, its topography, and numerous other factors. These unexpected hits also threaten the Japanese energy industry.

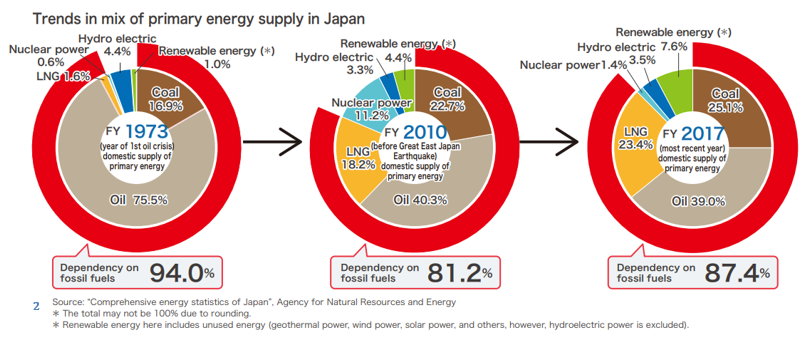

The energy situation in Japan is profoundly affected by outside factors. For instance, following the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami that caused serious damage to the Fukushima nuclear plant in 2011, Japan had to become more dependent on imports. This dependence gradually rose to 87.4% in 2017 since the incidents and the aftermath of them ( Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, 2019). Besides, Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, 2019 states that “Ratios of dependence on imports for fossil fuels in 2018 were 99.7% for oil, 97.5% for LNG (liquefied natural gas) and 99.3% for coal.”

In addition, one has to mention the incident at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa, which was another result of a damaged nuclear plantation by an earthquake in 2007 (Nakano, 2012). These incidents also changed the public view on nuclear energy, urging Japan to shut down its nuclear reactors and forcing Japan to find alternatives to its energy policy. Since 2011, a total number of 21 nuclear were decommissioned (Nippon, 2020).

When it comes to how independent Japan appears in terms of its energy suppliance, it is lower than in most OECD countries. Japan's Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (2020a) reports that ''In 2017, Japanʼs self-sufficiency ratio was 9.6%.'' Japan is an energy importer, so much so that in 2019, it was the fourth-largest crude oil importer in the world (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2020). EIA also reports that Japan's total energy production was 2.214 quadrillions Btu, and its total energy consumption was 19.414 quadrillion Btu in 2017 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2017). To be able to meet the demands, Japan has been importing especially fossil fuels from abroad.

Challenges over energy can also be described as the challenges over energy security. For Japan, there are other energy security concerns that are beyond its borders. Another big issue over Japanese energy imports is that most of the crude oil comes from politically unstable Middle Eastern countries in addition to the unsecured environment in the region. For example, in 2019 Japanese tanker got attacked by two flying objects in the Gulf of Oman (Reuters, 2019).

The latest concerns on energy security come from one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century, COVID-19. As the virus outbreak crashed almost every country's economic schemes, it also hindered the Japanese one. This impact weakens the energy demand in a cycle with economic weakness. In their report, Suehiro and Koyama (2020) argue that prior to the lockdowns, the energy demand was higher, giving a hint that the larger the lockdown scale will get, the prominent the negative impact will be on the energy market.

What Does Japan's Energy Policy Mean?

To answer this question, one has to study Japan's energy profile and Japan's journey on its energy technology advancement. As mentioned earlier, factors such as the challenges decrease the self-sufficiency over energy in Japan and guiding Japan to act accordingly. The global economies require to balance the supply-demand chain, particularly after the virus outbreak. Whether it is the uncertainty within politics or the outcomes of the lockdowns, COVID-19 has been a challenge for Japan from multiple aspects; thus, encouraging Japan to diversify its energy sources.

Looking at Japan's basic energy policy, one can easily conclude that the initial goal Japan wants to reassure is energy security to ensure safety. Lacking self-sufficiency and being dependent causes safety issues; consequently, Japan is shaping the Japanese basic energy policy until 2030 and 2050 to concentrate on this matter.

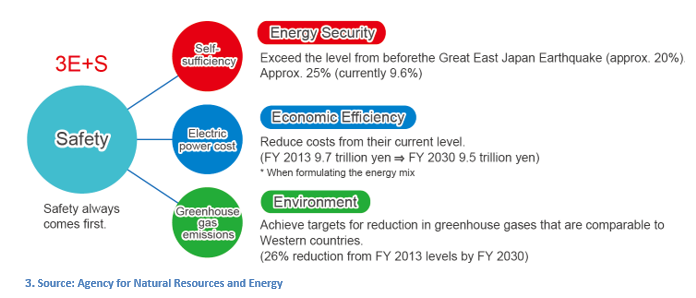

The significant targets that have been set within the framework of basic energy policy till 2013 are ''greenhouse gas reduction of 26% and reliable energy mix'' and to reach these goals, Japan's basic policy objectives were outlined (EU-Japan Centre). Illustrated above as 3E+S, these objectives also set targets for the long term energy policies till 2050. Since the 2030 targets that were set by the Paris Agreement, Japanese authorities emphasized the importance of their response to global warming; moreover, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, as Anadolu Agency (2020) reported ‘’vowed to cut carbon emissions to net zero by 2050’’.

To reduce carbon emissions, another big industry Japan wants to integrate within its energy profile is renewable energy alternatives. Since Japan is willing to reduce its dependence on imports, plus it needs to meet sustainability goals, renewables seem to fit into the Japanese strategy quite well. Energy security is one of the main pillars of becoming a self-sufficient consumer; hence, in case of another energy crisis as the 1973 oil crisis, or rising competition and prices caused by other emerging consumers, renewable energy appears to be the right investment option even when a crisis hits.

COVID-19 pandemic has been an indicator that renewable energy is a safe energy option in the long run; nevertheless, despite Japanese energy policies that lean towards renewables, they still only make up 6% of Japanese total energy consumption in 2019, shown in the first graph from earlier. One of the most important reasons behind the small percentages of renewables is that Japan is still in favor of nuclear energy since it is environmentally friendly and more efficient than renewables. Natural factors are affecting the performance of renewable energy sources, such as the change in weather or climate, lowering the expectations from their outcomes.

The most remarkable power generation has been the production of nuclear energy for Japan. Up until the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, Japan was the world's third-largest nuclear energy producer, and ''nuclear generation played a pivotal role in Japan’s electricity generation mix and accounted for 26% of net generation in the two years before Fukushima'' (EIA, 2020). Nevertheless, with the developments following the disaster, the Japanese energy policy shifted towards more nuclear-free approaches.

Knowing how big the Japanese nuclear energy sector was, one can also argue that in one way or another, Japan has long-term plans in support of the resurrection of this sector within its energy policy. Both as a notable necessity and as an environmentally friendly solution, Japan is aware of its inadequacy for nuclear energy generators; furthermore, operating most of its dormant reactors is still an option for Japan.

As a part of its energy policy, Japan also tends to invest in hydrogen energy. Hydrogen energy can be generated from different sources, and it is environmentally favorable since it doesn't emit carbon dioxide. Besides transporting hydrogen from Brunei, Japan also plans to reconstruct Fukushima with a new framework, the renewables, and hydrogen (Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, 2020b). This initiative, combined with the implementation of domestic energy strategies (e.g. construction hydrogen stations) and proposals of international cooperation, moves Japan towards a more hydrogen-based society.

When it comes to natural resources, Japan appears to be limited; nonetheless, there is one thing Japan is far from being restricted. The advanced technological developments of Japan have proved as an international partner for many countries within their energy projects. By providing the right methods in engineering, finance, and construction, Japan finds opportunities for energy investments abroad thanks to its energy research and development initiatives.IEEFA (2017) discusses the position and stresses on the aftereffects of the nuclear disaster in 2011 that led the Japanese energy policy to carry its expertise over renewable energy abroad. This strategy also allows Japanese foreign affairs to increase their influence on the rest of the world.

Last but not least, the Japanese policies within the region show signals of the Japanese interest in capturing regional energy resources. Specifically, the growing disputes over eight islands in the East China Sea have been warming up the waters, showing the interest over an estimated 200 million barrels of oil reserves (Council on Foreign Relations, 2020). For Japan, having access to these resources is vital, regarding its contribution to the Japanese energy outlook; nevertheless, the tension is rising in the region, leaving either side without any outcomes.

3.CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Japan's energy has various advantages and disadvantages as a consumer. On the one hand, one of the main benefits Japan has over other countries is the fact that Japan is a country devoted to technology and research. As a developed country, Japan has the financial and capital resources to discover solutions to the challenges it faces; moreover, there are a number of initiatives to make Japan a more sustainable, eco-friendly energy producer as well as consumer.

On the other hand, Japan is highly dependent on energy imports, which creates countless struggles for Japanese energy security. It is a liability for Japan to get through challenges from natural disasters to global crises. Being aware of the status-quo, Japan is forming targets and policies to overcome these challenges and design a future where it can survive within the emerging powers while maintaining its sustainable energy policies.

REFERENCES

[1]. Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, (2019). 2019 – Understanding the current energy situation in Japan (Part 1). Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/special/article/energyissue2019_01.html

[2]. Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, (2020a). JAPAN'S ENERGY 2019. Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. p.1 https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/brochures/pdf/japan_energy_2019.pdf

[3]. Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, (2020b). Hydrogen Energy Update A promising image of a “hydrogen-based society” is emerging now. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/special/article/detail_153.html

[4]. Anadolu Agency, (2020). Japan’s premier vows zero carbon emissions by 2050. Anadolu Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/japan-s-premier-vows-zero-carbon-emissions-by-2050/2019400

[5]. Council on Foreign Relations, (2020). Tensions in the East China Sea. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/tensions-east-china-sea

[6]. EIA, (2020). JAPAN. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/JPN

[7]. EU-Japan Centre, (2020). JAPAN’S NEW BASIC ENERGY PLAN UNTIL 2030 APPROVED. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.eu-japan.eu/news/japans-new-basic-energy-plan-until-2030-approved

[8]. IEEFA, (2017). IEEFA Update: Japan Is Investing Heavily in Overseas Renewables. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://ieefa.org/ieefa-update-japan-investing-heavily-overseas-renewables/

[9]. Kanaya, A. and Woo, D. (2000). Japanese Banking Crisis of the 1990s: Sources and Lessons. IMF. p.8 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2000/wp0007.pdf

[10]. Nakano, (2012). Japanese Energy Policy One Year Later. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/japanese-energy-policy-one-year-later

[11]. Nippon, (2020). Japan’s Nuclear Power Plants. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00238/japan%E2%80%99s-nuclear-power-plants.html#:~:text=Since%20the%202011%20disaster%20Japan's,of%20energy%20output%20by%202030.

[12]. Reuters, (2019, June 14). 'Flying objects' damaged Japanese tanker during attack in Gulf of Oman. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-tanker-japan-damage-idUSKCN1TF0M9

[13]. Suehiro and Koyama (2020). An Estimate on Impact of a ''City Lockdown'' on Japan's Energy Demand. P.1-4 https://eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/8898.pdf

[14]. The Japan Times, (2020, September 21). Older people account for record 28.7% of Japan's population. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/09/21/national/elderly-japan-population-record/

[15]. Tripp, P. (2017). JAPAN'S ENERGY CONSUMPTION CHALLENGES. Retrieved November 19, 2020 from https://asiancenturyinstitute.com/environment/1311-japan-s-energy-consumption-challenges

[16]. U.S. Energy Information Administration, (2017). Analysis - Energy Sector Highlights. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://www.eia.gov/international/overview/country/JPN

[17]. U.S. Energy Information Administration, (2020). Country Analysis Executive Summary:

Japan. EIA. https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Japan/japan.pdf

[18]. Walia, (2019, November 13). How Does Japan’s Aging Society Affect Its Economy?. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2019/11/how-does-japans-aging-society-affect-its-economy/

[19]. Worldometer, (2020). Japan Population. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/japan-population/

[20]. World Population Review, (2020). GDP Ranked by Country 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/countries-by-gdp

Melda Belkıs KÜPELİ

Güney Güvenlik Okulu Asya-Pasifik Masası Sorumlusu.